Exhibition Room 3

Daily Life Before Liberation

J-Koreans endeavored to maintain Korean lifestyles and traditions in Japan. It is not surprising that they would bring over the customs they were used to from their homeland. Women in particular preferred Korean traditional clothes and made the dishes they had eaten in their hometowns.

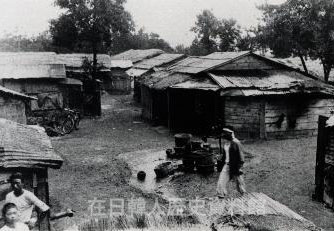

As Japanese often refused to rent rooms to Koreans, it was common for Koreans to build their own houses or to live in close proximity to each other on the outskirts of town. In order to assist each other amidst persistent Japanese discrimination, Koreans formed their own living communities. However, people were often forced to live without basic infrastructure such as water, sewage, and electricity. There were also only one or two toilets per community, which came to be seen as a sanitary problem.

Even so, the Korean neighborhoods contained shops for Korean groceries, Korean clothes, and Korean meals. Work placement services were also available. They were a refuge for Koreans in Japan, a place where they could speak Korean without worry and gather together. They were also centers for organizing labor and nationalist movements.

Considering the harsh conditions of Japan, such neighborhoods allowed Koreans to continue the ethnic traditions they had inherited from their homeland.

Greengrocer in Tokyo(1920s)

A Koreatown in Kamiishihara, Chofu-cho, Tokyo (1930s)

Daily Life After Liberation

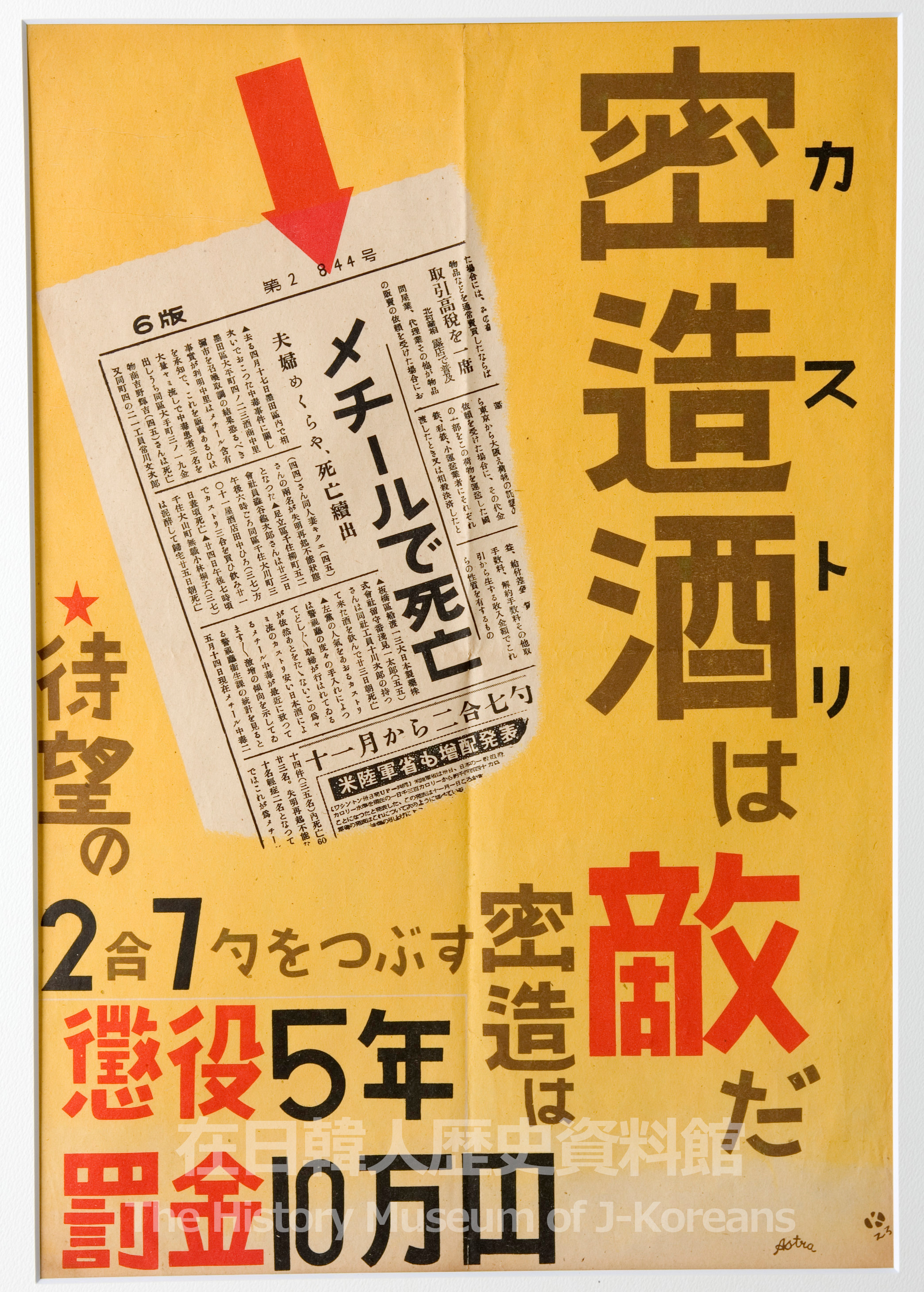

Immediately after liberation, Zainichi Koreans had no choice but to rely only on each other to obtain essentials such as food, clothes, and jobs. In 1952, there were 525,803 Zainichi Koreans, but few of them had fixed jobs, and 61% were unemployed. The largest percentage of those with jobs, 6.6%, worked as day laborers called nikoyon. Others worked jobs such as collecting waste materials; purchasing food from the countryside while riding crowded trains; buying and selling on the black market; operating food stalls; peddling; brewing doburoku, a type of alcohol made from rice; making low-grade alcohol called kasutori; selling candy; raising pigs; and so on. First-generation Zainichi Koreans engaged in all kinds of hard labor just to survive and make a living in Japan. However, the Japanese government cracked down on such activities, characterizing them as criminal and antisocial in nature.

Poster warning people that making kasutori is illegal (1948).

The fine of 100,000 yen was very heavy for the time.

Pachinko ball renting machine and Pachinko machine

(1960s)

Cultures and Customs Passed on from Generation to Generation

It is said that ethnic cultures and traditions tend to be preserved even more in foreign countries. Even within the shifting environment of Zainichi Korean society, the cultures and customs of Korea have been inherited from generation to generation. Although they lived on foreign soil, Zainichi Koreans upheld the traditional ceremonies for coming of age, marriages, funerals, and ancestral worship.

Many first generation immigrants treasured the items they brought with them from Korea such as brass bowls, vessels, and tables for memorial services. Despite the fact that most brass bowls were collected during wartime, they strove to keep their bowls from being taken away from them. This was probably due to their nostalgia for their homeland and their strong pride in the culture and traditions of Korea.

The majority of Zainichi families observe the ancestor memorial ceremony called jesa, where family members assemble on the anniversary of the parents’ and grandparents’ deaths in order to pay tribute to their ancestors. The format follows the teachings of Confucianism. There are many days for jesa such as New Year (& Lunar New Year), death anniversaries, and the harvest festival called Chuseok. In the past, there were some families that had a jesa more than once a month. The rites have changed over the years, but many third and fourth generation Zainichi Koreans still try to maintain these traditions as a way of respecting the bonds of the family.

Wedding ceremony between Yeon-hyung Cho

and Sun-ja Kim (1961)

jesa table and folding screen from Korea(1930s)

Ondol Reproduction

The ondol is an underfloor heating system that uses exhaust heat created, for example, when cooking with a furnace in an adjoining kitchen. It has long been used throughout the Korean peninsula and the northeastern part of China.

Most households in Korea had an ondol, and some Zainichi Koreans who moved to Japan during the 1920s and 1930s created their own ondol rooms.