Exhibition Room 2

The Great Joy of Liberation and Return

On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allied Powers and Korea finally saw the liberation of their homeland through Japan’s acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration. Soon after liberation, the majority of Koreans in Japan rushed back to their homeland to escape the unfair and difficult conditions of life in Japan.

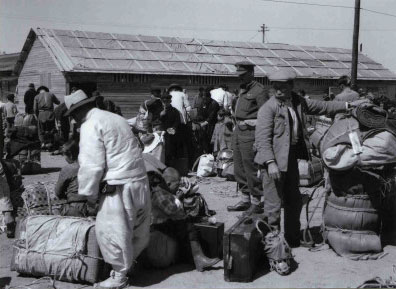

Since the Japanese government did not map out a systematic plan to transport Koreans to Korea, a massive crowd of Koreans camped out near ports such as Hakata and Senzaki waiting for ships to take them home. The land near the piers were packed with people who slept outdoors as they waited to get on a ship. Diseases spread as excrement flooded the streets. Possessions that could be taken to Korea were limited to 1000 yen and 150 pounds of luggage per person. Within one short year, 1,300,000 Koreans had returned to Korea.

Fukuoka Prefecture Hakata Port: Embracing liberation, people wait to return home. Around 500,000 people returned to the Korean peninsula in the first year from this port. (Hideaki Kimura, ed., Photographs of Postwar Fukuoka Taken by the Occupation Forces)

Yamaguchi Prefecture Senzaki Port: People returning from Senzaki. Over 300,000 people returned home in the first year from this port. These photos were taken by occupation forces from New Zealand. (Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand)

Korean Ethnic Pride

After liberation, many Koreans returned to their homeland but about 700,000 people remained in Japan due to the social instability in Korea and the restrictions on belongings for return. This marked the beginning of the postwar Zainichi (“residing in Japan”) situation. Due to the shutdown of the munitions industry after Japan’s war defeat and the return of former Japanese settlers, most Zainichi Koreans lost their jobs and immediately found themselves facing new hardships.

Zainichi Koreans continued to live in poor conditions in the immediate postwar period, but their hearts were full with hope. Many ethnic organizations were formed in various places in Japan, and Zainichi Koreans engaged in a diverse range of activities dedicated to eventually returning to their homeland and finding solutions to the problems that confronted them. The two most prominent J-Korean organizations were the pro-North Korea Chōren (The League of Koreans in Japan) and the pro-South Korea Mindan (the Korean Residents Union in Japan), reflecting the divided occupation of the peninsula by US and Soviet forces.

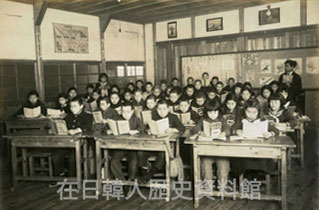

Many Zainichi Koreans strongly wanted to return to their homeland in the future. In order to do that, they had to teach uri mal (the Korean language) to children who had been born and raised in Japan and who could only understand Japanese, a language that had been forced upon them under the imperial educational system. Even amidst the lack of teachers, buildings, and teaching material, a movement to build schools that would allow Koreans to reclaim their national language arose with the motto “Wisdom from those with wisdom, strength from those with strength, money from those with money!” 600 Korean ethnic schools were built throughout Japan and approximately 60,000 children studied there.

Koreans in Yamagata Prefecture after liberation

Korean ethnic school established in 1945

(Yachimata, Chiba Prefecture)

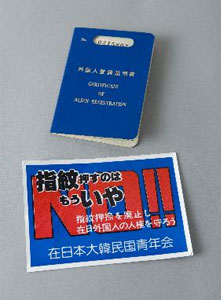

The Anti-Fingerprinting Campaign

On May 2, 1947, an Alien Registration Ordinance (the last imperial ordinance, or chokurei) was promulgated for the purpose of managing and monitoring Koreans in Japan. It became the Alien Registration Act after the San Francisco Peace Treaty (April 1952). Zainichi Koreans were required to carry their alien registration card at all times, and there was a stiff penalty for anyone who failed to do so. Also, for those over 14 years old, there was a fingerprinting system (changed to over 16 years old in 1982) in which the fingerprints of all 10 fingers of both hands were collected every 3 years.

In September 1980, Jong-seok Han of Tokyo refused to be fingerprinted as prescribed in the Alien Registration Act, calling it a “brand of humiliation.” It was initially called “the resistance of a single soul.” However, support of this resistance soon arose among the younger generation, spreading even among Japanese people, and became one of the iconic social movements of the 1980s. The Ministry of Justice tried to suppress the growing movement, using repressive methods that included arrest, denial of re-entry permits, and denial of residence applications under the pretext of maintaining the law.

In 1985, the number of those refusing or withholding their fingerprinting surpassed 10,000 people. The Japanese government sought to deflect criticism by making small revisions such as replacing the black ink with an aqueous solution and limiting the fingerprinting to one time only. In April 2000, the fingerprinting requirement under the Alien Registration Act was finally abolished.

On September 10, 1980, Jong-seok Han (passed away on

July 24, 2008) refused to be fingerprinted. This photo is

from a protest meeting that was convened after he was

convicted in his trial over the Alien Registration Act

(August 1984).

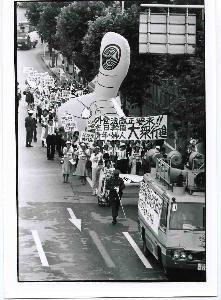

A protest march against the Alien Registration Act

organized by Zainichi Korean youth and women’s groups

(October 1984)

Zainichi Koreans Active in Japanese Society

Despite the many barriers that stood in their way, Zainichi Koreans accomplished much in their personal and professional lives. While many paths to public office are still closed to them, there has been an increase in the number of Korean residents active in the various cultural spheres of Japan, particularly in the entertainment industry, various artistic fields, sports, and other fields where ability and not ethnicity is privileged as the most important factor.

The Akutagawa Prize and Naoki Prize are Japan’s two most prestigious literary awards. To date, four Zainichi Korean authors have received the Akutagawa Prize; four have been awarded the Naoki Prize. “Zainichi literature” has even become its own genre.

Some say that you could form the strongest baseball team by putting all the Zainichi Korean players on one team; or that the Kōhaku uta gassen, an annual NHK singing contest on New Year’s Eve, would not be possible without Zainichi Koreans. Iconic figures include Rikidōzan, who was a professional wrestler in postwar Japan; Isao Harimoto, a baseball player who holds the record for most hits in the Japanese professional leagues; and Akiko Wada, who has appeared over 20 times on the annual Kōhaku uta gassen. Many might be surprised by the long list of prominent celebrities who are actually Zainichi Koreans. However, there are still some Zainichi Koreans who feel that they cannot reveal their roots. That is proof that discrimination remains.

Rikidōzan at Shokudōen in Osaka (third from right)

Violin master maker Chang-hyeun Jin